SYLLABI

Fertile Bodies: Reproduction from Antiquity to the Enlightenment

Spring 2023 Course Syllabus (Penn)

Spring 2022 Course Syllabus (Princeton)

Spring 2020 Course Syllabus (Princeton)

The ancient Greeks imagined a woman’s body ruled by her uterus, while medieval

Christians believed in a womb touched by God. Renaissance anatomists hoped to uncover the

‘secrets’ of human generation through dissection, while nascent European states wrote

new laws to encourage procreation and manage ‘illegitimate’ offspring.  From ancient Greece to enlightenment France, a woman’s womb served as a site for the production of medical

knowledge, the focus of religious practice, and the articulation of state power.

In this course students traced the evolution of medical and cultural theories about women’s

reproductive bodies from ca. 450 BCE to 1700, linking these theories to the development

of structures of power, notions of difference, and concepts of purity that proved

foundational to ‘western’ culture. Students read selections from Hippocrates’ Diseases

of Women 1, Galen’s On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body, Augustine’s Confessions,

The Trotula, Aristotle’s Masterpiece, and William Harvey’s Disputations

Touching the Generation of Animals.

From ancient Greece to enlightenment France, a woman’s womb served as a site for the production of medical

knowledge, the focus of religious practice, and the articulation of state power.

In this course students traced the evolution of medical and cultural theories about women’s

reproductive bodies from ca. 450 BCE to 1700, linking these theories to the development

of structures of power, notions of difference, and concepts of purity that proved

foundational to ‘western’ culture. Students read selections from Hippocrates’ Diseases

of Women 1, Galen’s On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body, Augustine’s Confessions,

The Trotula, Aristotle’s Masterpiece, and William Harvey’s Disputations

Touching the Generation of Animals.

History of Science: Scientific Revolutions

What is science, anyway? Is it a kind of knowledge? A methodology? A set of beliefs? For hundreds of years, well before the word “science” became synonymous with the experimental method or laboratories, humans investigated the natural world and sought to understand why it worked the way it did. But the brightest minds of the ancient, medieval, and Renaissance eras didn’t call themselves “scientists” (though the root of our modern word science does come from an ancient word: scientia, meaning “wisdom” in Latin). Ancient thinkers like Plato or Aristotle didn’t separate their inquiries into the natural world from their inquiries into ethics or morality, and medieval writers were very eager to think about theology right alongside astronomy, medicine, and botany.

What is science, anyway? Is it a kind of knowledge? A methodology? A set of beliefs? For hundreds of years, well before the word “science” became synonymous with the experimental method or laboratories, humans investigated the natural world and sought to understand why it worked the way it did. But the brightest minds of the ancient, medieval, and Renaissance eras didn’t call themselves “scientists” (though the root of our modern word science does come from an ancient word: scientia, meaning “wisdom” in Latin). Ancient thinkers like Plato or Aristotle didn’t separate their inquiries into the natural world from their inquiries into ethics or morality, and medieval writers were very eager to think about theology right alongside astronomy, medicine, and botany.

Between 1500 and 1800, however, a new philosophy and methodology for interrogating the natural world developed in western Europe. This methodology, based in empiricism, observation, reason, and experimentation, was notably different from the intellectual work done by poets or artists or theologians. Over time, this way of investigating the natural world became associated with “objectivity” and demonstrable “facts,” the concepts that have given science a monopoly on truth in our contemporary world. In some popular versions of this story, science triumphed over superstition, to include the superstition of religious belief.

This course investigates the origins of science as a way of knowing and asks how this body of knowledge gained widespread cultural authority. Though it features big names like Andreas Vesalius, Galileo Galilei, and Isaac Newton, it also centers scientists working in artisanal workshops or household kitchens. And though we’ll remain focused on “Western” science as it developed in Europe, we’ll see that this body of knowledge emerged through interactions with goods, ideas, and peoples from across the wider world.

Check back in Fall of 2025 for links to episodes of students’ podcast episodes, debunking myths about the relationship between religion and science in early modern Europe. They’ll be featured in season 5 of TCU’s History Frogcast!

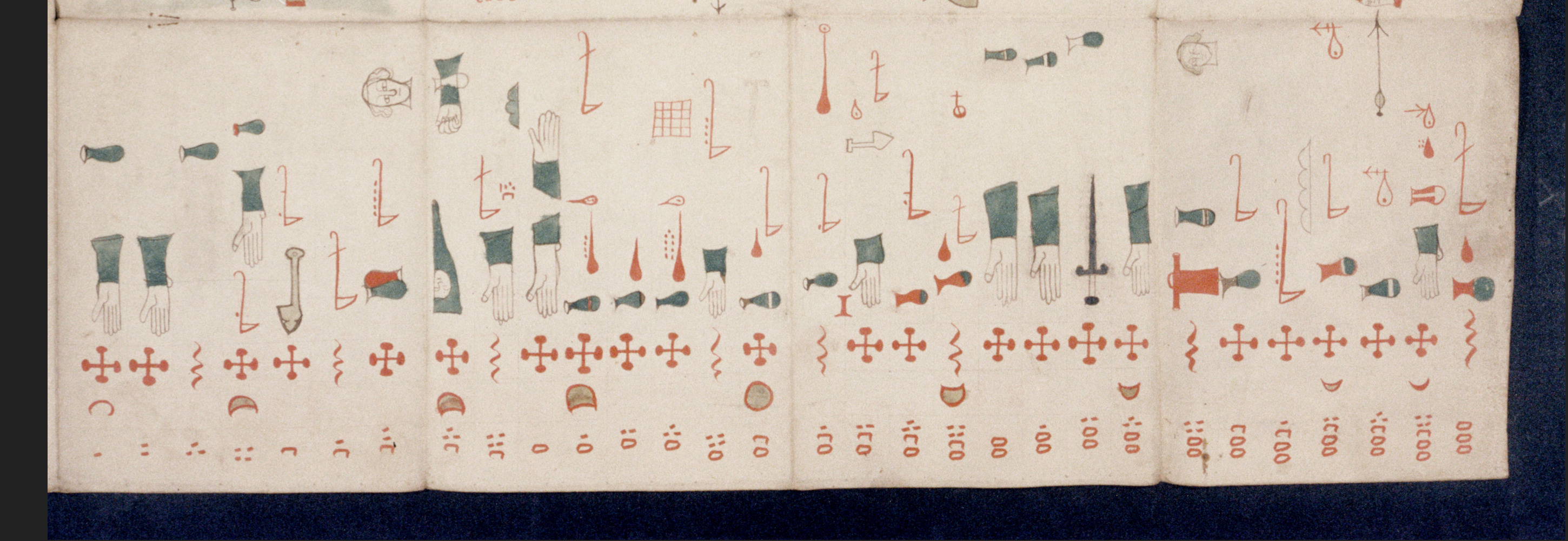

Technologies of History from Cuneiform to Coding

This digital humanities course was first developed in 2021 with a David A. Gardner ‘69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council at Princeton University. You can view the Spring 2021 course website to read Princeton students’ work.

This digital humanities course was first developed in 2021 with a David A. Gardner ‘69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council at Princeton University. You can view the Spring 2021 course website to read Princeton students’ work.

Now taught at TCU, “Technologies of History” asks how the ways that humans communicate—via inscription, graffito, letter, or Tweet—have the power to affect society and make history. We explore the history of communications technologies from the invention of writing to the printing press to social media, and each week, we pair these topics with analysis of a cutting-edge digital archive or project. Students then learn how to use the “digital tools” reflected in these projects, building the skills necessary to produce their own works of digital historical scholarship. You can view the Spring 2026 syllabus here or check out student work produced in the course on our blog.

The course thus has two interconnected aims: to introduce students to the history of communications technology from the ancient Near East to the modern U.S. and to interrogate how contemporary digital communications technologies shape our study of the creation, circulation, and transmission of historical knowledge. Close engagement with digital archives allows students to view and appreciate the material texts of the past, but it also forces students to analyze how digital archives make historical arguments through the representation and presentation of sources. Students learn about the limitations of digital archives, both as representations of material objects and as ephemeral—and often fragile—sources in their own right, while also developing the digital skills to create their own works of historical scholarship for publication.